The multipolar expansion model is based on exact formulas for the solvation energy of a point multipole in a spherical cavity,782, 461 which is a crude approximation except (or perhaps even) for small molecules, and the Kirkwood-Onsager model has been largely superseded by the more general class of “apparent surface charge” SCRF solvation models, typically known as PCMs.1125, 461 These models improve upon the multipolar expansion method in two ways. Most importantly, they provide a much more realistic description of molecular shape, typically by constructing the “solute cavity” (i.e., the interface between the atomistic region and the dielectric continuum) from a union of atom-centered spheres, an aspect of the model that is discussed in Section 11.2.3.2. In addition, the exact electron density of the solute (rather than a multipole expansion) is used to polarize the continuum. Electrostatic interactions between the solute and the continuum manifest as an induced charge density on the cavity surface, which is discretized into point charges for practical calculations. The surface charges are determined based upon the solute’s electrostatic potential at the cavity surface, hence the surface charges and the solute wave function must be determined self-consistently.

The PCM literature has a long history1125 and there are several different models in widespread use; connections between these models have not always been appreciated.203, 155, 204, 627, 461 Chipman203, 204 has shown how various PCMs can be formulated within a common theoretical framework; see Ref. 461 for a review. The PCM takes the form of a set of linear equations,

| (11.2) |

in which the induced charges at the cavity surface discretization points [organized into a vector in Eq. (11.2)] are computed from the values of the solute’s electrostatic potential at those same discretization points. The form of the matrices and depends upon the particular PCM in question. These matrices are given in Table 11.3 for the PCMs that are available in Q-Chem.

| Model | Literature | Matrix | Matrix | Scalar |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refs. | ||||

| COSMO | 573 | |||

| C-PCM | 1137, 64 | |||

| IEF-PCM | 203, 155 | |||

| SS(V)PE | 203 | |||

| Also includes a charge renormalization correction; see Section 11.2.8. | ||||

The oldest PCM is the so-called D-PCM model of Tomasi and coworkers,780 but unlike the models listed in Table 11.3, D-PCM requires explicit evaluation of the electric field normal to the cavity surface. This is undesirable, as evaluation of the electric field is both more expensive and more prone to numerical problems as compared to evaluation of the electrostatic potential. Moreover, the dependence on the electric field can be formally eliminated at the level of the integral equation whose discretized form is given in Eq. (11.2).203 As such, D-PCM is essentially obsolete, and the PCMs available in Q-Chem require only the evaluation of the electrostatic potential, not the electric field.

The simplest PCM that continues to enjoy widespread use is the conductor-like model, C-PCM.64, 230 Originally derived by Klamt and Schüürmann573 based on arguments invoking the conductor limit (), this model can also be derived as an approximation to more formally correct models.202, 626, 461 Over the years, the dielectric-dependent factor

| (11.3) |

that appears in this model (see Table 11.3) has been used with different values of . The value is typically used in C-PCM calculations and in COSMO calculations, although Klamt and co-workers later suggested using for neutral solutes and for ions.572 The specific choice of is controllable via the $pcm input section that is described in Section 11.2.4.

Whereas from Table 11.3 the C-PCM and COSMO methods would appear to be the same up to a minor rescaling of the surface charge (i.e., up to the precise choice of ), historically the term “COSMO" has been used by Klamt to mean a particular “dual-cavity” implementation of this model that makes it different from other PCMs.461 This construction is equivalent to the “outlying charge correction” that is discussed in Section 11.2.8, and was intended to account for the effects of the tail of the solute’s charge density that penetrates beyond the cavity surface.571 Subsequent work cast considerable doubt on the theoretical justification for this correction, since the C-PCM/COSMO ansatz was shown to include already an implicit correction for outlying charge.202, 461 Further discussion of this construction and of COSMO is deferred to Section 11.2.8,

As compared to C-PCM, a more sophisticated treatment of continuum electrostatic interactions is afforded by the “surface and simulation of volume polarization for electrostatics” [SS(V)PE] approach.203 Formally speaking, this model provides an exact treatment of the surface polarization (i.e., the surface charge induced by the solute charge that is contained within the solute cavity, which induces a surface polarization owing to the discontinuous change in dielectric constant across the cavity boundary) but also an approximate treatment of the volume polarization (arising from the aforementioned outlying charge). The “SS(V)PE” terminology is Chipman’s notation,203 but this model is formally equivalent, at the level of integral equations, to the “integral equation formalism” (IEF-PCM) that was developed originally by Cancès et al..154, 1126 Some difference do arise when the integral equations are discretized to form finite-dimensional matrix equations,627 and it should be noted from Table 11.3 that SS(V)PE uses a symmetrized form of the matrix as compared to IEF-PCM. The asymmetric IEF-PCM is the recommended approach,627 although only the symmetrized version is available in the isodensity implementation of SS(V)PE that is discussed in Section 11.2.6. That said, differences between symmetry and asymmetric versions are only important in the case of van der Waals cavity surfaces; they are insignificant for the isodensity cavity construction.461

As with the obsolete D-PCM approach, the original version of IEF-PCM explicitly required evaluation of the normal electric field at the cavity surface, but it was later shown that this dependence could be eliminated to afford the version described in Table 11.3.203, 155 This version requires only the electrostatic potential, and is thus preferred, and it is this version that we designate as IEF-PCM. The C-PCM model becomes equivalent to SS(V)PE in the limit ,203, 627 which means that C-PCM must somehow include an implicit correction for volume polarization, even if this was not by design.571 For , numerical calculations reveal that there is essentially no difference between SS(V)PE and C-PCM results.627 Since C-PCM is less computationally involved as compared to SS(V)PE, it is the PCM of choice in high-dielectric solvents. The computational savings relative to SS(V)PE may be particularly significant for large QM/MM/PCM jobs. For a more detailed discussion of the history of these models, see the lengthy and comprehensive review by Tomasi et al..1125 For a briefer discussion of the connections between these models, see Refs. 204, 627, 457.

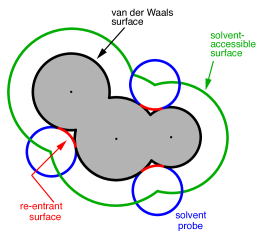

Construction of the cavity surface is a crucial aspect of PCMs, as computed properties are quite sensitive to the details of the cavity construction. Most cavity constructions are based on a union of atom-centered spheres (see Fig. 11.1), but there are yet several different constructions whose nomenclature is occasionally confused in the literature. Simplest and most common is the van der Waals (vdW) surface consisting of a union of atom-centered spheres. The radius for the sphere centered on atom can be written in the form

| (11.4) |

where is the vdW radius for atom , taken for example from the set of vdW radii published by Bondi.121 Traditionally, the vdW radii that are extracted from crystallographic data are scaled by a factor –1.2.120, 1127, 461 This 20% augmentation is intended to mimic the fact that solvent molecules cannot approach all the way to the vdW radius of the solute atoms, though it’s not altogether clear that the same value ought to be optimal in all cases. (The scaling factor defaults to but can be modified by the user.)

An alternative to scaling the atomic radii is to add a certain fixed increment to each, representing the approximate size of a solvent molecule, and leading to what is known as the solvent accessible surface (SAS). The choice Å is common for water and represents the approximate physical size of a water molecule, although values in the range –0.5 Å often afford better solvation energies.461 In any case, if a nonzero value of is used, then the scaling factor in Eq. (11.4) should be set to , since these two parameters are intended to model the same effect, namely, that a solvent molecule’s finite size prevents it from approaching all the way to the vdW radii of the solute.

Note from Fig. 11.1 that both the vdW surface and the SAS possess cusps where the atomic spheres intersect, although these become less pronounced as the atomic radii are scaled or augmented. These cusps are eliminated in what is known as the solvent-accessible surface (SES), sometimes called the Connolly surface or the “molecular surface". The SES uses the surface of the probe sphere at points where it is simultaneously tangent to two or more atomic spheres to define elements of a “re-entrant surface” that smoothly connects the atomic (or “contact”) surface.622

Having chosen a model for the cavity surface, this surface is discretized using atom-centered Lebedev grids645, 646, 643 of the same sort that are used to perform the numerical integrations in DFT. (Discretization of the re-entrant facets of the SES is somewhat more complicated but similar in spirit.622) Surface charges are located at these grid points and the Lebedev quadrature weights can be used to define the surface area associated with each discretization point.624

A long-standing (though not well-publicized) problem with the aforementioned discretization procedure is that it fails to afford continuous potential energy surfaces as the solute atoms are displaced, because certain surface grid points may emerge from, or disappear within, the solute cavity, as the atomic spheres that define the cavity are moved. This undesirable behavior can inhibit convergence of geometry optimizations and, in certain cases, lead to very large errors in vibrational frequency calculations.624 It is also a fundamental hindrance to molecular dynamics calculations.625 Building upon earlier work by York and Karplus,1257 Lange and Herbert624, 625, 622 developed a general scheme for implementing apparent surface charge PCMs in a manner that affords smooth potential energy surfaces, even for ab initio molecular dynamics simulations involving bond breaking.625, 457, 461 Notably, this approach is faithful to the properties of the underlying integral equation theory on which the PCMs are based, in the sense that the smoothing procedure does not significantly perturb solvation energies or cavity surface areas.624, 625 The smooth discretization procedure combines a switching function with Gaussian blurring of the cavity surface charge density, and is thus known as the “Switching/Gaussian” (SwiG) implementation of the PCM.

Both single-point energies and analytic energy gradients are available for SwiG-PCMs, when the solute is described using molecular mechanics or an SCF (Hartree-Fock or DFT) electronic structure model, except that for the SES cavity model only single-point energies are available. Analytic Hessians are available for the C-PCM model only. (As usual, vibrational frequencies for other models will be computed, if requested, by finite difference of analytic energy gradients.) Single-point energy calculations using correlated wave functions can be performed in conjunction with these solvent models, in which case the correlated wave function calculation will use Hartree-Fock molecular orbitals that are polarized in the presence of the continuum dielectric solvent (i.e., there is no post-Hartree–Fock PCM correction). This represents a “zeroth-order” inclusion of solvent effects that captures the leading-order effect of continuum solvation on molecular properties. Given the crudeness of the model itself, more consistent inclusion of post-Hartree–Fock solvation effects is not expected to be important.461

Researchers who use these PCMs are asked to cite Refs. 625 and 627, which provide the details of Q-Chem’s implementation, and Ref. 622 if the SES is used. We point the reader in particular to Refs. 625 and 1261, which provides an assessment of the discretization errors that can be anticipated using various PCMs and Lebedev grids; default grid values in Q-Chem were established based on these tests. When publishing results based on PCM calculations, it is essential to specify both the precise model that is used (see Table 11.3) as well as how the cavity was constructed, and this should be done without resorting to software-specific keywords, the use of which has significantly muddled the literature on continuum electrostatics.233, 461 As an example of good practice, the default cavity construction in Q-Chem is a vdW cavity using Bondi atomic radii,121 except that for hydrogen we use the modified radius of 1.1 Å, following a reassessment that judged Bondi’s original value of 1.2 Å for hydrogen to be too large.980 Each of these radii in Eq. (11.4) is then scaled by a factor for use in cavity construction. Radii for main-group elements that were not provided by Bondi are taken from Ref. 732. Absent details such as these, PCM calculations will be difficult to reproduce in other electronic structure programs.

In vertical excitation or ionization, the solute undergoes a sudden change in its charge distribution. Various microscopic motions of the solvent have characteristic times to reach certain polarization response, and fast part of the solvent response (electrons) can follow such a dynamic process while the remaining degrees of freedom (nuclei) remain unchanged as in the initial state. Such splitting of the solvent response gives rise to nonequilibrium solvation. In the literature, two different approaches have been developed for describing nonequilibrium solvent effects: the linear response (LR) approach151, 228 and the state-specific (SS) approach.1127, 152, 226, 502 Both are implemented in Q-Chem,1261,at the SCF level for vertical ionization and at the corresponding level (CIS, TDDFT or ADC, see Section 7.11.10) for vertical excitation. A brief introduction to these methods is given below, and users of the nonequilibrium PCM features are asked to cite Refs. 1261 and 776. State-specific solvent-field equilibration for long-lived excited states to compute e.g. emission energies is implemented for the ADC-suite of methods as described in Section 7.11.10. Users of this equilibrium-solvation PCM please cite and be referred to Ref. 775.

The LR approach considers the solvation effects as a coupling between a pair of transitions, one for solute and the other for solvent. The transition frequencies when the interaction between the solute and solvent is turned on may be determined by considering such an interaction as a perturbation. In the framework of TDDFT, the solvent/solute interaction is given by489

| (11.5) |

where is the charge density response function of the solvent and is the solute’s transition density. This term accounts for a dynamical correction to the transition energy so that it is related to the response of the solvent to the charge density of the solute oscillating at the solute transition frequency (). Within a PCM, only classical Coulomb interactions are taken into account, and Eq. (11.5) becomes

| (11.6) |

where is PCM solvent response operator for a generic dielectric constant, . The integral of and the potential of the density gives the surface charge density for the solvent polarization.

The state-specific approach takes into account the capability of a part of the solvent degrees of freedom to respond instantaneously to changes in the solute wave function upon excitation. Such an effect is not accounted for in the LR approach. In SS, a generic solvated-solute excited state is obtained as a solution of a nonlinear Schrödinger equation

| (11.7) |

that depends upon the solute’s charge distribution. Here is the usual Hamiltonian for the solute in vacuum and the reaction field operator generates the electrostatic potential of the apparent surface charge density (Section 11.2.3.1), corresponding to slow and fast polarization response. The solute is polarized self-consistently with respect to the solvent’s reaction field. In case of vertical ionization rather than excitation, both the ionized and non-ionized states can be treated within a ground-state formalism. For vertical excitations, self-consistent SS models have been developed for various excited-state methods,502, 750 including both CIS and TDDFT.

In a linear dielectric medium, the solvent polarization is governed by the electric susceptibility, , where is the frequency-dependent permittivity. In case of very fast vertical transitions, the dielectric response is ruled by the optical dielectric constant, , where is the solvent’s index of refraction. In both LR and SS, the fast part of the solvent’s degrees of freedom is in equilibrium with the solute density change. Within PCM, the fast solvent polarization charges for the SS excited state can be obtained by solving the following equation:226

| (11.8) |

Here is the discretized fast surface charge. The dielectric constants in the matrices and (Section 11.2.3.1) are replaced with the optical dielectric constant, and is the potential of the solute’s excited state density, . The quantity is the potential of the slow part of the apparent surface charges in the ground state, which are given by

| (11.9) |

For LR-PCM, the solvent polarization is subjected to the first-order changes to the electron density (TDDFT linear density response), and thus Eq. (11.8) becomes

| (11.10) |

The LR approach for CIS/TDDFT excitations and the self-consistent SS method (using the ground-state SCF) for vertical ionizations are available in Q-Chem. The self-consistent SS method for vertical excitations is not available, because this method is problematic in the vicinity of (near-) degeneracies between excited states, such as in the vicinity of a conical intersection. The fundamental problem in the SS approach is that each wave function is an eigenfunction of a different Hamiltonian, since Eq. (11.7) depend upon the specific state of interest. To avoid the ordering and the non-orthogonality problems, we compute the vertical excitation energy using a first-order, perturbative approximation to the SS approach,150, 157 in what we have termed the “ptSS” method.776 The zeroth-order excited-state wave function can be calculated using various excited-state methods (currently available for CIS and TDDFT in Q-Chem) with solvent-relaxed molecular orbitals obtained from a ground-state PCM calculation. As mentioned previously, LR and SS describe different solvent relaxation features in nonequilibrium solvation. In the perturbation scheme, we can calculate the LR contribution using the zeroth-order transition density, in what we have called the “ptLR” approach. The combination of ptSS and ptLR yields quantitatively good solvatochromatic shifts in combination with TDDFT but not with the correlated variants of ADC, for which the pure ptSS approach was shown to be superior.1261, 776

The LR and SS approaches can also be used in the study of photon emission processes.503 An emission process can be treated as a vertical excitation at a stationary point on the excited-state potential surface. The basic requirement therefore is to prepare the solvent-relaxed geometry for the excited-state of interest. TDDFT/C-PCM analytic gradients and Hessian are available.

Section 7.3.5 for computational details regarding excited-state geometry optimization with PCM. An emission process is slightly more complicated than the absorption case. Two scenarios are discussed in literature, depending on the lifetime of an excited state in question. In the limiting case of ultra-fast excited state decay, when only fast solvent degrees of freedom are expected to be equilibrated with the excited-state density. In this limit, the emission energy can be computed exactly in the same way as the vertical excitation energy. In this case, excited state geometry optimization should be performed in the nonequilibrium limit. The other limit is that of long-lived excited state, e.g., strongly fluorescent species and phosphorescence. In the long-lived case, excited state geometry optimization should be performed with the solvent equilibrium limit. Thus, the excited state should be computed using an equilibrium LR or SS approach, and the ground state is calculated using nonequilibrium self-consistent SS approach. The latter approach is implemented for the ADC-based methods as described in Section 7.11.10.

For ultrafast processes in solution, such as electron transfer, photo-absorption/emission and photo-ionization, a continuum model should combine a proper nonequilibrium solvation theory to account for nonequilibrium solute–solvent interactions. In the traditional treatments, the nonequilibrium electrostatic solvation free energy was derived from the so-called reversible electric work integration along the path linking the initial equilibrium state (eq) and the intermediate nonequilibrium state (neq),743, 744 i.e.,

| (11.11) |

where denotes the total electric potential including both the potential due to the solute charge in vacuum and polarization potential due to the medium. In order to deal with electron absorption and emission spectra in solution, the numerical expression of nonequilibrium solvation free energy which was established by intuitively collecting a series of energy terms from the interactions of solute charges and polarized charges, has been implemented using TDDFT with PCM model.226, 227 It is easy to verify this numerical form can be achieved through the discretization of analytical expression of nonequilibrium solvation energy by traditional treatments.684 However, there exist a number of doubts on the overestimation of the solvent reorganization energy in ultrafast processes by this reversible electric work method.111, 384 It becomes clear now that there is no possibility to find a reversible pathway between the initial equilibrium state and the intermediate nonequilibrium state. Thus, the integrated electric work can not equal to the change of electrostatic free energy.684

Xiangyuan Li et al.684, 683, 1236, 956 established the new theory for nonequilibrium solvation by employing the constrained equilibrium principle668 using the following pathway

| (11.12) |

where C stands for the constrained equilibrium state which is constructed and mapped to the true nonequilibrium state by introducing the proper external charge which is used to equilibrate the “residual” polarization potential, . In this way the solvent reorganization energy can be derived as

| (11.13) |

Then the nonequilibrium solvation free energy is simply given by

| (11.14) |

For more detailed descriptions of the gain of the external (constraining) charge , or the equivalent constraining external electric field , please refer to the review.684 Within the framework of continuum model, the discretization and numerical solution of Eq. (11.14) is expressed as109

| (11.15) |

where the subscript denotes the ground ( = 1) or excited ( = 2) electronic state. The value refers to the solute electrostatic potential at the mth tesserae. is the apparent charge for the nonequilibrium state. is the square matrix based on PCM versions (CPCM, IEFPCM, SSVPE, etc.).

The vertical excitation energy for absorption is defined as

| (11.16) |

where stands for total free energy of the solute in solution,

| (11.17) |

is calculated by the self-consistent reaction field (SCRF) method based on equilibrium ground-state reaction field and means ground-state electronic energy of the solute. Based on the equilibrium ground-state reaction field, with a self-consistent state-specific method in the framework of TDDFT, is given by109

| (11.18) |

is the excitation energy from TDDFT calculation.Alternatively, based on the nonequilibrium excited-state reaction field, is given by108

| (11.19) |

where represents the th iteration of the nonequilibrium excited-state reaction field at the ground-state geometry of solute. is the excitation energy from TDDFT calculation in the presence of the nonequilibrium excited-state reaction field. stands for the ground-state electronic energy of solute at the th iteration. Clearly, Eq. (11.19) is more physically-meaningful than Eq. (11.18).

Similarly, the vertical excitation energy for emission is given by108

| (11.20) |

where and represent the free energies of the equilibrium excited state and the nonequilibrium ground state at the excited-state equilibrium geometry, respectively, which can be expressed as108

| (11.21) |

| (11.22) |

can be directly obtained by TDDFT calculation in the equilibrium excited-state reaction field at the th iteration and is the corresponding ground-state electronic energy of the solute. is the ground-state electronic energy of the solute at the excited-state equilibrium geometry in the presence of the nonequilibrium ground-state reaction field.

The keyword TdNonEq is requested in the $pcm section. Refs. 684 should be cited if constrained equilibrium principle is employed to obtained the vertical absorption/emission energies in solution using the self-consistent state-specific (SS)-PCM/TDDFT method.